Despite changes, organizations claim roadblocks to police records remain

Despite the repeal of a mechanism meant to make access to police records easier, some organizations say roadblocks remain.

•

Jun 24, 2021, 2:24 AM

•

Updated 1,280 days ago

Share:

More Stories

1:27

What's Cooking: Uncle Giuseppe's quiche lorraine

231ds ago2:34

Guide: Safety tips to help prevent home burglaries

295ds ago1:31

What's Cooking: Uncle Giuseppe's Marketplace's prime rib roast

378ds ago2:19

Guide: Safety measures to help prevent fires and how to escape one

443ds ago2:07

Tips on how to avoid confrontation with sharks while swimming in the ocean

527ds ago2:33

5 tips to prevent mosquito bites and getting sick from viruses

538ds ago1:27

What's Cooking: Uncle Giuseppe's quiche lorraine

231ds ago2:34

Guide: Safety tips to help prevent home burglaries

295ds ago1:31

What's Cooking: Uncle Giuseppe's Marketplace's prime rib roast

378ds ago2:19

Guide: Safety measures to help prevent fires and how to escape one

443ds ago2:07

Tips on how to avoid confrontation with sharks while swimming in the ocean

527ds ago2:33

5 tips to prevent mosquito bites and getting sick from viruses

538ds agoDespite the repeal of a mechanism meant to make access to police records easier, some organizations say roadblocks remain.

It's been just over a year since New York got rid of a controversial part of its civil rights law, 50-a, that created a special right to privacy for police officers, corrections officers, firefighters and paramedics.

50-a was officially repealed on June 12, 2020, one month after George Floyd was killed by former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin. A murder that sparked calls for police reform across the nation and here in New York.

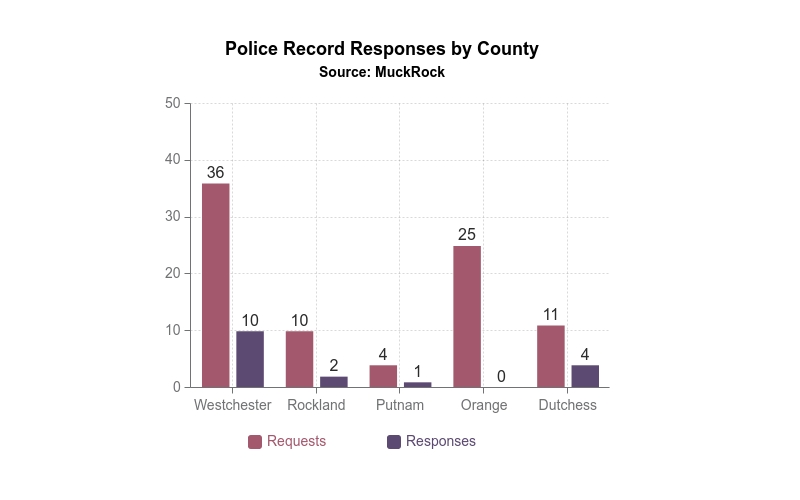

Repealing the law was supposed to make it easier for the public to get access to police disciplinary records to increase transparency within local departments and help regain trust in law enforcement. But ongoing data and FOIL requests from organizations like MuckRock prove otherwise.

The nonprofit sent FOIL (Freedom of Information Law) requests to 400 police departments across the state. Only 40, 10%, responded within six months of New York repealing 50-a. Ongoing data shows similar results.

"The law is the law. Here's the simple issue, what are they afraid of, that people will know the truth?" asks Randolph McLaughlin, a law professor at Pace University.

In the year since tossing out 50-a, police departments and local municipalities have come up with new ways to fight the release of disciplinary records.

Some departments have requested tens of thousands of dollars to cover the cost of organizing and redacting documents, others say ongoing lawsuits prevent them from releasing documents, some say they don't keep any records and others either don't respond or push back release dates - according to MuckRock data.

"They're claiming that's part of the FOIL law but I think it's just an effort to stop people from getting access to the records that they need to determine whether or not their police department is functioning efficiently, constitutionally, or abusively," said McLaughlin.

Just this past spring the Middletown Police Department pushed back against a FOIL request for officer disciplinary records. A judge ordered the department to release the documents, but the city's attorney is appealing and claiming they need clarification about how far back the request can go.

"We respect the law, the law has been changed and we'll abide by it. We didn't agree with it then and we still don't agree with it now," said Detective Keith Olson, president of the Affiliated Police Associations of Westchester, a nonprofit law enforcement organization representing 4,000 officers in the county.

"The repeal of 50-a didn't change existing laws that exist in New York like the FOIL laws," adds Olson.

Some Hudson Valley departments are now digging into the state's FOIL laws.

Some, including Somers, Croton-on-Hudson and Rhinebeck, have responded to MuckRock's requests. Others, like Harrison ($7,635 for 27,500 pages of documents and labor) and Yonkers ($30,815 for 1,000 pages and labor) are requesting massive payment to release documents.

"I kind of find it ironic that the same people that are pushing for this information under 50-a are the same people that are trying to protect the rights of criminals and protect the information of criminals," said Olson.

So, if repealing 50-a didn't fix the transparency, what will?

McLaughlin says litigation and creating more civilian complaint review boards.

"If you want people to obey the law, make them pay when they don't obey the law," said McLaughlin.

Westchester has only one CCRB, located in Ossining.

Last summer ProPublica and the New York Civil Liberties Union released 300,000 New York Police Department misconduct documents they received after FOIL requests to the NYC Civilian Complaint Review Board.

"CCRB is probably going to turn over the records more readily [and] more accessibly than municipalities," said McLaughlin.

These independent agencies are tasked with receiving, investigating and reporting on misconduct allegations against police.

McLaughlin says they're more likely to release information to the public because they have less legal liability than the police or individual municipality.

But Olson and other top police officials see it differently. They believe people are taking advantage of the law change and putting good cops at risk.

"In one movement they're trying to protect the rights and help criminals while at the same time trying to forfeit the rights of police officers and that's not good at all," said Olson.

Thus the battle between police accountability and vulnerability continues.

More from News 12

3:49

Grand jury declines to file charges against police officers who shot motorist in New Jersey

3:50

Shooting of unarmed motorist by Bloomfield police will be investigated by grand jury

2:06

Justice for All: Police body cameras spark in-depth discussion during town hall event

21:03

Justice For All Town Hall: Have reforms gone far enough following George Floyd's murder?

4:03

Justice for All: Men of Elmont work to encourage conversations between police, community

4:01